Published on October 13, 2021 by Umang Aggarwal

A little inflation is always considered healthy. Why? For two key reasons:

(1) it is expected to amplify consumption as the purchasing power of future cash flow reduces and

(2) it prompts increased investment, enlarging the overall economic pie.

But how much inflation is good inflation? This is a topic that has gained attention recently, especially as global pricing prints have increased since the start of the pandemic. The bigger question is whether the real inflation rate is sitting on a permanently higher trajectory. The answer is critical to determining an expected economic growth trajectory for the US, as it would feed into mortgage costs, stock market volatility, consumption sentiment and overall growth potential.

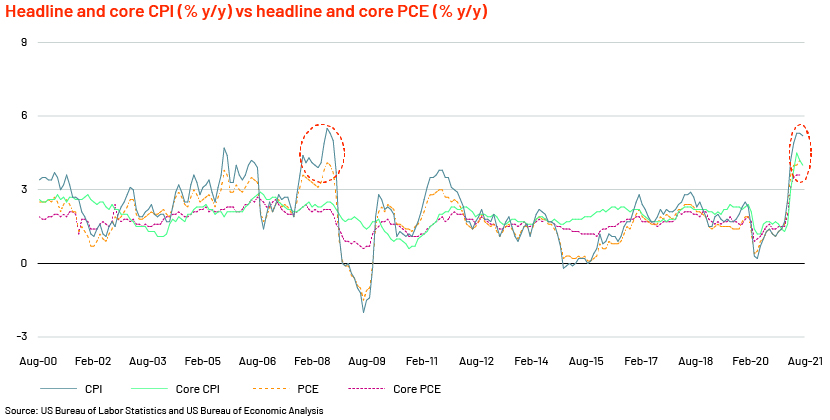

The Fed has a loosely defined flexible average inflation-targeting framework that aims for a 2% target rate [stated usually in terms of personal consumption expenditure (PCE)] over the long run but is accommodative during periods of volatility and disruption, especially when price increases are assumed to be largely transient. This is interesting because PCE has historically trended lower than consumer price inflation (CPI), which may give some credibility to the Fed’s 2% framework as not being conservative (see figure below).

PCE is generally seen as a better measure because the spending composition better depicts actual consumer behaviour. However, more attention is paid to CPI because it is used to adjust social security payments and is also the reference rate for certain financial contracts, such as Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) and inflation swaps. Whether we measure CPI or PCE, it is evident that current inflation prints are running as high as they were in 2008 and the 1990s

This year through August 2021, inflation has jumped to an average of 3.8% in headline and 3% in core. Interestingly, if we look only at the latest three months, inflation is significant at 5.3% in headline and 4.2% in core, the highest in 30 years, excluding inflation in 2008, before the financial crisis. Evidently, the current inflation story, whether seen through CPI or PCE, seems to be misaligned with the Fed’s narrative of it being transient.

Is inflation really transient?

Since the first prints that caused concern over inflation, the Fed has remained dovish on changes in interest rates along with the stimulus regime. The Fed only recently ended two of its unemployment benefits programmes that covered gig workers and individuals who had been jobless for more than six months, leading to close to 8m people losing these benefits. This, interestingly, has run parallel to an increase in jobless claims, driven by Hurricane Ida and the spread of the delta variant. This is likely to prevent any imminent hawkish Fed surprises (rate hike expectations are already for 2023). We can, therefore, expect both demand-pull and cost-push inflation in the coming months.

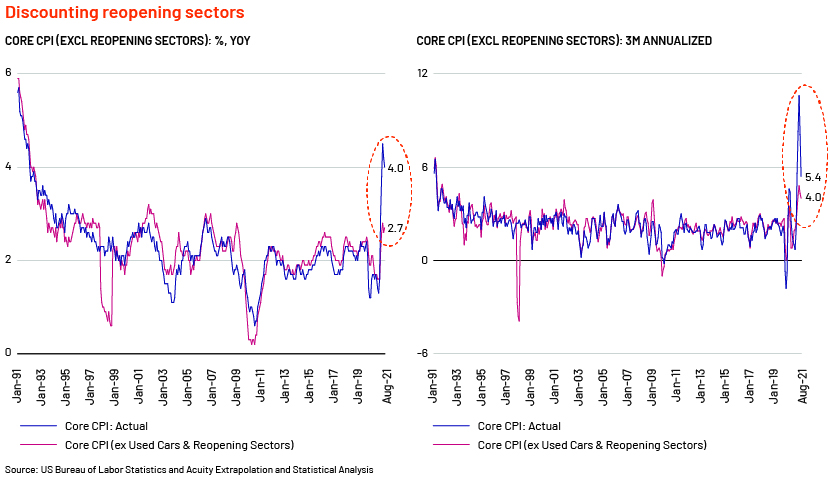

The Fed believes the current inflation spikes are a result of temporary bottlenecks, largely supply-related, as the US economy reopens after the pandemic-induced shutdown. While, one may accept this line of thought in part, inflation remains at levels far above the trend expected pre-pandemic. To understand this, we take a look only at those sectors that are reopening, namely airfares, used cars, entertainment, recreation and lodging and take into account core inflation to discount for the effects of the more volatile food and energy sectors. Extrapolating this data, it is clear that even after discounting for these sectors, core CPI remains significantly high, suggesting that these effects may be less than transitory. Core CPI excluding the reopening sectors would be 4.2% in y/y terms and a whopping 8.1% in annualised terms, suggesting all may not be as simple as the Fed makes it out to be.

While the Fed Chair has already stressed that that the criteria for tapering are quite different from what is required for rate lift-off, and that inflation is not the sole consideration, it is imperative to acknowledge that inflation is ballooning and a return to pre-pandemic levels may not be as smooth or easy as expected, especially when the situation has been exacerbated by a withdrawal of benefits and Hurricane Ida.

Will delta bring another blow?

Economists, analysts and research houses are of the opinion that while prices will see a downward movement, the magnitude of such a movement may not be significant, meaning that the new price normal will likely be above the pre-pandemic trend and industries and suppliers will eventually adjust to this new normal . Timothy Fiore, chairman of the Institute for Supply Management Manufacturing Business Survey Committee gives examples of price increases in natural gas, fuel and hot rolled coil, stating that the new price normal will likely be even higher.

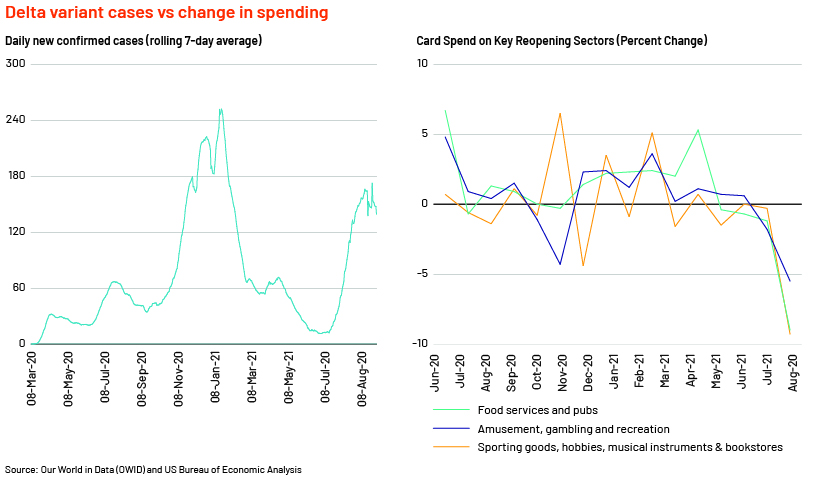

Added to this is the issue of rising delta variant cases in the US that could delay a full reopening of the economy. During the Fed meeting, participants highlighted the uncertainty relating to the delta variant and the possibility that it could exacerbate supply and delivery challenges, constraining growth. These shortages have contributed to large price increases and the highest rate of inflation rate since 2008.

A case in point would be mapping card spending data for reopening sectors such as sports, amusement parks and restaurants to new COVID-19 cases (see figure above). Spending in all reopening sectors has fallen sharply from recent peaks, declining more than during the severe winter COVID-19 wave, when spending was at much lower levels. Slightly positive is the modest softening in restaurant spending. We expect this scenario to peak in a month’s time, considering the experiences of the UK and emerging markets, a situation most unwelcome when supply shortages have already led to a spike in raw material prices and are likely to continue to do so.

That said, the spread of the delta variant may not be seen as severe but is likely to add to the current inflation woes, even if modestly. It is likely to temporarily delay the full reopening of the economy and restrict hiring and labour supply, when unemployment benefits have already been rescinded.

What it means for the global economy

The Fed’s view that the current pricing concerns are nothing but concerns is probably based on its focus on reviving economic lethargy and the roiled unemployment sector. That said, it would be fair to conclude that inflation expectations are climbing higher but at present unlikely to concern the Fed all that much.

However, the global economy is unequivocally tied to developments in the US, and any change to the monetary policy environment would affect the global marketspace. At current levels, the issue is more about supply disruptions and productivity slowdown than about rising prices since industries have continued to accept higher prices. On the other hand, a continued rise in inflation could lead to an earlier Fed rate hike. A rise in US interest rates would imply capital outflow from the US as a more lucrative investment option – leading to USD appreciation and inflation elsewhere. Such capital outflow will likely result in financial market volatility in those countries, with an increased risk of higher interest rates, slower growth and currency depreciation.

Another issue would be paying back debt that has been issued in USD. As the USD becomes expensive, overall debt plus interest would balloon, making the possibility of defaulting or at least deferring payment more real. This would hold true for both private borrowers and official (or government) borrowers. Knowing all this and likely repercussions, we really need to ask, How much is too much?

How Acuity Knowledge Partners can help

Global organisations and research houses leverage our industry- and country-specific experience to make sound strategic decisions. We set up dedicated teams of analysts and macro-level associates to support our clients in a wide range of areas including macroeconomic research, industry profiling, financial analysis, econometric modelling, thematic research, building databases and providing regular sector coverage. Each output is customised, based on the client’s requirement, and made available for their exclusive use. This ensures our clients a unique, sustainable edge.

Sources:

1. Federal Reserve Economic Data: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/

2. https://www.ismworld.org/supply-management-news-and-reports/reports/ism-report-on-business/

3. JP Morgan and Chase Report “US Weekly Prospects”, 6 August 2021

4. Our World in Data: Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) – the data - Statistics and Research - Our World in Data

5. Bureau of Economic Analysis: COVID-19 and Recovery: Estimates From Payment Card Transactions | U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA)

What's your view?

About the Author

Currently working as a Delivery Manager in the private equity domain with expertise in areas of economics and financial modelling. Her work experience spans over 7 years with hand-on knowledge in subjects related to economics, consulting, and public finance at international, national, and state level. This includes extensive functional knowledge of macro-economic modelling, financial analysis, econometrics, and public finance.

As an Economist, she overlooks global economic outlook, especially for India, US, Euro Area, and Asia-Pacific.

She has contributed significantly in developing points of view around several key economic issues and events for CII and AMCHAM; has co-authored papers and articles on India Economic Outlook, Voice..Show More

Like the way we think?

Next time we post something new, we'll send it to your inbox